Listening to this clip sends me into a nostalgic dwam. In fact, I don't remember listening to 'Listen With Mother'. I do remember listening to MY mother. I know I was read to as a child, by both parents, and remember very strongly the feeling of not wanting the story to end, of not wanting the precious one-to-one time to stop because of something inconvenient like the advance of sleep with its dark smothering blanket... No, no, tell me more about how the wolf escapes from those horrible three little pigs, please, please... But I digress.

My own mother - Frances Campbell - presented a television series in the early '60s for Scottish Television, called For The Youngest Scot. She would read a story, make a toy or a diorama from some scraps of material or other household objects (a circular box from those triangles of Dairylea cheese became a glittering miniature roundabout, complete with cut-out horses that whirled round a central pole; a small handbag mirror became an icy loch surrounded by twigs with green sponge for foliage and cotton wool for snow). For each day of the week there was a differently dressed doll.

"What day is it? Can you remember? It's the milkmaid doll, so it's... a Tuesday."

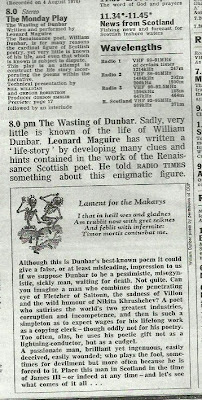

Alas, STV in their wisdom appear to have wiped them all. We still have somewhere a page from the Radio Times circa 1964, a promotional photo in which, with carefully coiffed hair, Ma is featured demonstrating her Scottish and motherly qualities for the camera.

Alas, STV in their wisdom appear to have wiped them all. We still have somewhere a page from the Radio Times circa 1964, a promotional photo in which, with carefully coiffed hair, Ma is featured demonstrating her Scottish and motherly qualities for the camera.I've been thinking and writing a lot about my father's work and influence recently, and of course my mother's work and influence matter just as much, even if there are fewer ways to demonstrate it. (Thanks, STV.) (Hey! Watch the sarcasm! Ed.) This doll for instance, is not one that Ma used from the TV programme but a doppleganger found years later and with great joy in a local charity shop.

Our childhoods are constructs, aren't they? Formulated from real memories, amplified by significant and treasured objects, held together by a large amount of information gathered later from variously un/reliable sources, filtered through our imaginations.

However they're composed, they're real to us, and their effects may often be present in how we view the world, what moves us or drives us, throughout our later lives.

I 'remember' lying in my childhood bedroom, looking up at a loved (if weary) face telling me a story, but that probably comes from my mother telling me about her reading to me, about her difficulty in staying awake as she tried to get me to 'close your bloody little eyes' and go to sleep... another layer of that memory might come from a visit in the early '90s to our old house (in Edinburgh's Regent Terrace, the building which is now the Norwegian Consulate). The shape of the room, the way the light came through the window, all felt familiar, even though the rose-strewn wallpaper and twin beds with pink cotton chenille bedspreads and puffy quilts had been replaced by bland office furnishings.

Memory and the past can often feel like lobster traps, tricky to negotiate a way into and even trickier to exit. On the other hand, if you're as cunning or persistent as, say, an octopus, or an otter, you're probably able to visit and leave at will. One of the things my mother produced for children's radio was dramatised readings from books by a former neighbour, Major-General R.N. Stewart, who wrote about salmon and wildlife and boats and the Yukon and huskies and... some of the books were anthropomorphic tales, others were practical and adventurous and For Boys. I was a tomboy and I liked them. It was my mother's working with the General's books at the BBC that led to our family moving, for a while, to live in Ardnamurchan. That, in my memory, was mostly a very happy time.

Memory and the past can often feel like lobster traps, tricky to negotiate a way into and even trickier to exit. On the other hand, if you're as cunning or persistent as, say, an octopus, or an otter, you're probably able to visit and leave at will. One of the things my mother produced for children's radio was dramatised readings from books by a former neighbour, Major-General R.N. Stewart, who wrote about salmon and wildlife and boats and the Yukon and huskies and... some of the books were anthropomorphic tales, others were practical and adventurous and For Boys. I was a tomboy and I liked them. It was my mother's working with the General's books at the BBC that led to our family moving, for a while, to live in Ardnamurchan. That, in my memory, was mostly a very happy time.But that's another story for another day. Listening time is over now, children.

ps - that obituary-link gets several facts wrong. I remember giving the information by phone, just after her funeral, to a young journalist who must have mixed up his details. It says there that my mother's participation in For The Youngest Scot was as producer; no, she was a producer/director of hundreds of children's programmes for BBC Radio Scotland, up until 1958, but she was the presenter only of this particular TV programme.